The Evolution of Cheesman Park, Part 1

- Alexandra Corlett

- Feb 5, 2022

- 12 min read

Updated: Feb 9, 2022

Bound by 8th and 13th Streets on the South and North flanks, respectively, and by the Humboldt-Franklin alley on the West and the High-Race alley on the East flank, sits one of Denver, Colorado’s most cherished city parks.

Joggers love Cheesman Park for the crushed granite jogging path that winds its way around the park. But it's also a popular spot for families, thanks to its large playground with swings, slides and everything else to delight your young ones. The park, located at Franklin St. and 8th St., also offers incredible vistas stretching from the Cheesman Memorial Pavilion to the Front Range.

So reads the description on denver.org, a website devoted to enticing people to visit the city. On the surface, there is nothing wrong with this description (except for their utter failure to mention that literally half the park’s visitors are dogs). Indeed, it is a well-furnished, wide-open space with truly stunning views of both the city and the mountains. But underneath that well-groomed lawn lies a dark and dirty history—and between 2,000 and 4,000 human bodies.

What follows is Part One of my three-part history of Cheesman Park in Denver, Colorado. Please note that despite my greatest efforts, my research is still incomplete. If you have any corrections, additions, anecdotes, or ghost stories about the history of Cheesman Park, feel free to leave them in the comments.

In late August of 1858, news of the discovery of gold in the Pike’s Peak region of Colorado (then still part of Kansas Territory) hit the headlines to the East like wildfire. Although the press was just as—if not more—prone to exaggeration in those times as it is today, the people of Kansas City and other parts of what is now Nebraska and Kansas had the benefit of seeing gold specimens from the new mining district firsthand as prospectors returned bearing both gold “float” from rivers and streams and mined quartz riddled with glimmering tendrils of the metal. Gold was also found on the South Platte River and Cherry Creek—the confluence of which today marks the western edge of East Denver, Colorado—shortly after Pike’s Peak made the news, and it quickly became clear that the Rocky Mountains were rich (Spring, 83). [1]

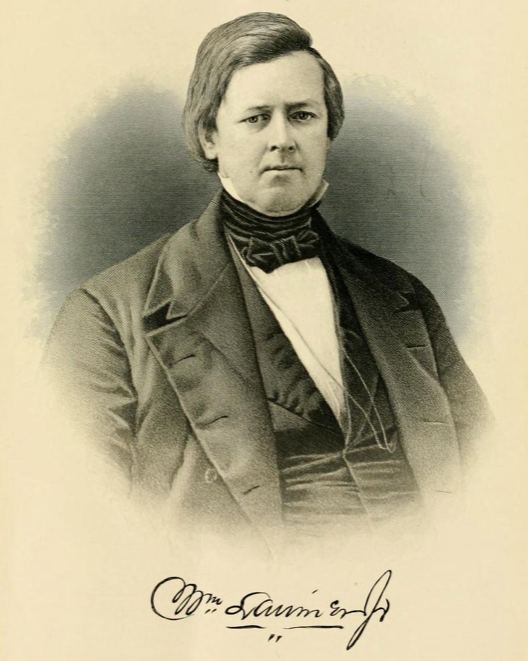

William Larimer and his two sons got swept up in this 1858 rush to the Rockies. Transplants from Pennsylvania, the Larimers were living in Leavenworth, Kansas when the news broke. Mr. Larimer was doing just fine, financially-speaking—he was working with railroad companies and was a huge proponent of expanding rail lines to the West—but his sons were just too excited about the idea of finding gold to let the opportunity pass, so Larimer organized a party of locals to head to Cherry Creek. [2]

William Larimer was a businessman. As a young adult in Pennsylvania, he had “embarked on many different business ventures,” such as managing a Conestoga wagon line, establishing a coal company and a wholesale grocery, founding both the Pittsburgh & Connellsville and the Remington Coal Railroads, and had also worked as a banker and innkeeper in Pittsburgh. Upon moving to Nebraska, he served on the Territorial Legislature from 1855 to 1856, and upon moving to Kansas in 1858, organized the Kansas Republican Party. All in all, he was a people person. He seemed to have a penchant for ensuring that everyone had access to a place where they felt they belonged. [2]

Larimer’s legacy did not stop when he and his group—known as the Leavenworth Party—arrived at the headwaters of Cherry Creek in November of 1858. Seeing a haphazard collection of tents and questionably-constructed log cabins dotting the banks of Cherry Creek, Larimer sought to improve the situation by creating order out of the typical mining-settlement chaos that had begun to plague the area. So, he moved to the East side of Cherry Creek. The West side of the creek had, just days before the Larimers arrived, been designated the town of Auraria. The East side had barely been settled; a group of pioneers had formed the St. Charles Town Company on September 24th, 1858 and had claimed the land on the East side of the creek with the intention of setting up a town there to be known as St. Charles. But Larimer found no evidence that their claim was valid, and found no members of the St. Charles Town Company present with whom to consult, so he and his son, William Henry Harrison, built themselves a log cabin at what would today be 15th and Larimer Streets. Eventually, the members of the St. Charles Town Company appeared, having returned from a trip back East for supplies, and a verbal scuffle broke out regarding whether or not Larimer was allowed to build upon and inhabit the St. Charles claim. Larimer won the dispute on the grounds that the St. Charles Company had no proof of a valid claim to the land. Shortly thereafter, on November 22nd, Larimer helped organize the Denver City Town Company, whose members quickly began to call what was once the town of St. Charles “Denver City” instead (Spring, 94-98). [1] [2]

After settling into their rustic abode in Denver City and giving the area the slightest semblances of a formidable civilization, William Larimer realized that Denver City, as all good cities do, needed a cemetery. Early in the spring of 1859, Larimer and his son, who he called Will, went in search of a good lot to be turned into a cemetery. They “staked one off on the hill along the road up Cherry Creek,” according to Will, which “seemed the most eligible site and not too far off (Davis, 150).” They named it Mount Prospect Cemetery. [3]

From its modest beginnings, Mount Prospect Cemetery was riddled with controversy. For starters, Will and Mr. Larimer, who had partnered with another Denver pioneer named William Clancy, had trouble keeping their claim on the cemetery land (Goodstein, 283). “A cabin was unnecessary for a graveyard,” Will wrote with regards to how he and his father might go about securing rights to the land, “dead bodies were necessary; so we watched quietly for the first victims (Davis, 151).” [3] [4]

They got their first victims, alright. On either April 7th or 8th, 1859, a young man by the name of Stoefel murdered Thomas Bieneroff, who was either his father-in-law or brother-in-law, on the banks of Clear Creek (near present-day Golden, Colorado). Stoefel’s trial ran the same day that he murdered Bieneroff; whether that was the 7th or 8th of April, we’ll never know, but he was sentenced to death by hanging and hung on April 8th, and on April 9th, the two men were buried at Mount Prospect Cemetery, in a spot hand-selected by the Larimers. They were buried together, in the same grave (Davis, 147-149; Goodstein, 284; Vickers, 187). [3] [4] [5]

Stoefel and Bieneroff were not the first permanent residents of Mount Prospect, however. Back in March, a fellow whose name was either Edward Hay or Abraham Kay had died suddenly—of “cold,” according to Will, or of a lung infection, according to Phil Goodstein—at his camp near the mountains and had been interred within the area the Larimers had staked off. “We thought we had triple grounds on which to base our claim to the cemetery property,” Will wrote with regards to the three bodies buried on their claim, “and it did prove satisfactory until an undertaker appeared on the scene and started an establishment for supplying coffins (Davis, 151; Goodstein, 283).” [3] [4]

The undertaker who Will says “appeared on the scene” was most likely John J. Walley, “a cabinetmaker who was called upon to make caskets,” according to Phil Goodstein. He became an undertaker by default, and “personally supervised many burials” at Mount Prospect. Goodstein writes that Walley was known for the “pinchtoe model,” a popular term for his method of squeezing a body into a casket—a technique Walley used often, owing to his regular practice of using as little lumber as possible to build his coffins (Goodstein, 284). [4]

Also according to Goodstein, the Larimers’ struggle to hold onto their claim of Mount Prospect Cemetery was intensified by emigrants trying to homestead the land, allowing their cattle to graze there at will (284). [4]

As the debate regarding who owned the cemetery raged on, the Catholic residents of Denver, seeking consecrated ground in which to bury their dead, bought 40 acres of Mount Prospect Cemetery on August 27, 1865—from John Walley, not the Larimers. They renamed their segment of the cemetery Mount Calvary. A year later, on August 3, 1866, the Jewish people of Denver decided that they wanted their own private sector of the cemetery, too, and purchased 10 acres from Walley. Their sector was commonly known as the Hebrew Cemetery (Goodstein, 284). [4]

To complicate matters, Congress decided to remind everybody involved in the dispute over who owned the land that it belonged to the federal government. In March of 1870, the United States Land Office annulled all claims to the cemetery land, citing the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie as proof that it was government land, and that the government had the ultimate say in what would be done with it (Goodstein, 284). (Oddly enough, the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie actually granted the land to the Plains Native Americans, not to the U.S. government, so their argument was moot, but nobody realized that at the time, apparently (Kappler; "Fort Laramie Treaty").) [4] [6] [7]

The City of Denver immediately began trying to buy the cemetery from the federal government, but they did not succeed in doing so until May 21, 1872—five days after William Larimer passed away. The 160-acre lot that Larimer and his son had staked out in Denver’s fledgling days was sold to the City at a whopping $1.25 per acre under the stipulation that it always be used as a cemetery. Consequently, it was renamed the Denver City Cemetery (Goodstein, 284). [4]

Upon the purchase of the cemetery land by the City of Denver, John Walley was suddenly in big trouble. He had, without having official rights to the land, sold 40 acres to the Catholic Church and 10 acres to the Jewish people of Denver. Thus, the first order of business was to ensure that these sales were legitimatized. On February 6, 1874, the Catholic Church re-purchased their 40 acres, paying exactly the same amount as the first time, and the Jewish people followed suit shortly thereafter. Walley continued to operate as an undertaker (Goodstein, 284). [4]

Other social and ethnic groups divvied up the land amongst themselves, leaving a large section of the north end of the land for general burials. Aside from the Catholic and Jewish peoples, the groups that secured their own sections of the City Cemetery included the Masons, Odd Fellows, and the Chinese, most prominently (Goodstein, 284; Arps). [4] [8]

Under the ownership of the City, the cemetery quickly fell into disrepair. “From the start,” Phil Goodstein writes, “stories floated about grave robbing and how medical students would snatch bodies.” Photos of the cemetery from that period show cracked and toppled headstones and weeds as tall as trees. Mount Calvary and the Hebrew Cemetery were relatively well-maintained, but the city-run portion of the cemetery was the epitome of the Wild West. “There were…problems with the burial of paupers,” according to Goodstein. “Often they would dig up” older pauper graves when interring a fresh body. “Disinterred corpses would occasionally be found lying on the street,” Goodstein writes (285). [4]

Needless to say, the City got sick of trying to take care of the cemetery. Everyone they hired bailed right off the bat, and crime was virtually uncontrollable. So, throughout the 1880s, the City of Denver began to pester Congress once again, pleading for a revision in the legal usage rights of the land to allow the City to turn it into a park. On January 25, 1890, Congress approved the City’s request. As a token of gratitude, the City renamed the old cemetery “Congress Park (Goodstein, 286).” [4]

But the City of Denver did nothing to improve the conditions of the park. After extending an open invitation to all families of the dead buried there to remove their dead to one of the other cemeteries that had sprung up over the years (Fairmount or Riverside), the city all but abandoned the cemetery. No deadline was enforced, no timeline explained—the people of Denver simply had all the time in the world, it seemed, to move their dead elsewhere (Goodstein, 286). [4]

By the early spring of 1893, however, there were still some 5,000 bodies buried at the old city cemetery. All of a sudden, the City of Denver decided that it was done waiting on its citizens to casually relocate their dead and hired an undertaker to oversee the process (Goodstein, 286). [4]

The man hired for the relocation of bodies was Edward P. McGovern. McGovern began working in the embalming and undertaking business in May of 1879 after years of working as a carpenter (Vickers, 516). Moving 5,000-plus bodies was a big job. He needed to fashion a new casket for transporting each body. He would be paid $1.90 for each casket made. Relocating the bodies, however, would prove to be quite challenging, since the old cemetery soil was underlaid with soft bentonite clay. Owing to that clay shrinking and swelling throughout the seasons, “a few bodies were discovered to have turned to upright positions” underground, Goodstein writes. Upon breaking the soil, McGovern was also tasked with surmounting several other difficulties, Goodstein notes: [5]

Often the bones of a skeleton were scattered around. Other times, bodies were not where they were supposed to be or more than one body occupied a grave. Evidence was discovered that graves had been robbed (286).

Despite the fact that “hundreds turned out to watch the gruesome job of digging up the bodies,” McGovern made the executive decision to up the ante on the repulsive factor, along with his personal profit from the nasty business, as Goodstein explains:

McGovern ordered his workers to skimp on the job. They used small coffins that were approximately one-foot high, two-feet wide, and three-feet long. His 18 employees were instructed to fill one coffin with a skull, another with an arm or a leg, a third with chest bones, and possibly a fourth with dirt and rocks (286)

It didn’t take long for the press to catch wind of the horrendous spectacle being performed by McGovern at the City Cemetery. Naturally, after a publicly humiliating account was told of it in the papers, McGovern was fired. Oddly enough, he was allowed to maintain his private undertaking and embalming business afterwards, and it turned out to be widely profitable (Goodstein, 286-287). [4]

After the McGovern scandal, the City of Denver announced, in August of 1893, that all graves must be vacated within 90 days, and if they were not, the dead would forever remain in-place (Goodstein, 287). [4]

At the time of this announcement, many Western states were teetering on the brink of financial collapse—the new President, Grover Cleveland, was working to eliminate federal spending on silver, which had been bringing in quite the profit for the State of Colorado since about 1879, as well as for other states (Nevada, namely). The U.S. government had been purchasing 4.5 million ounces of silver per month since July of 1890, owing to the passage of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. President Cleveland, however, who was inaugurated on March 4, 1893, “was not a fan of silver and believed that mandatory silver buying hurt the US economy,” since the increased spending on silver since 1890 had led to “drainage of gold in the US treasury,” according to Colorado Encyclopedia. In October, President Cleveland finally managed to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, thereby initiating a massive financial crisis in the Western states. As a result, the City of Denver, despite having issued a 90-day notice on evacuating its old cemetery grounds, had to then announce that, in fact, it would not have the funds to continue work on the creation of Congress Park. Once again, the park was left abandoned. [9] [10]

No progress was made on the conversion of the old cemetery to a city park until the late 1890s. The lot sat for years exactly how McGovern had left it: some graves open to the sky above, some untouched, and still others half-dug with coffins protruding and semi-dismembered, badly-decomposed corpses lying about. It was unsightly, and the city eventually installed a fence to prevent children from playing in the area, which had become a popular pastime, as photos will attest (Goodstein, 288). [4]

During that period of sitting, unused, amidst the rapidly-growing Capitol Hill neighborhood of Denver, it is said that ghostly figures could be seen walking across the lot late at night. Residents near the old cemetery reported strange occurrences in their homes. But these were only the beginning of the long-term side effects of the park’s dark history, and next Wednesday, I’ll tell you the rest (Goodstein, 287-288 & 306-322; Weiser). [4] [11]

Sources

[1] Spring, Agnes Wright. "Rush to the Rockies, 1859." Colorado Magazine, April 1959.

[2] Encyclopedia Staff. "William Larimer, Jr." Colorado Encyclopedia, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/william-larimer-jr. Accessed 03 February 2022

[3] Davis, Herman S., editor. Reminiscences of General William Larimer and of his Son William H. H. Larimer: Two of the Founders of Denver City. New Era Printing Company, 1918.

[4] Goodstein, Phil. The Ghosts of Denver: Capitol Hill. New Social Publications, Denver, 1996.

[5] Vickers, W. B. History of the City of Denver, Arapahoe County, and Colorado. O. L. Baskin & Co., Historical Publishers, Chicago, IL, 1880.

[6] Kappler, Charles J. United States. Dept. of Indian Affairs. "Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, Etc., 1851." Laws and Treaties, Vol. II, Government Printing Press, Washington, 1904, pp. 594-596.

[7] "Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 (Horse Creek Treaty)." National Park Services, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/horse-creek-treaty.htm. Accessed 03 February 2022.

[8] Arps, Louisa Ward. "Draft Copy of Cemetery to Conservatory." Denver Public Library Special Collections. Peterson, Bernice E., contributor, https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll4/id/1965. Accessed 03 February 2022.

[9] Encyclopedia Staff. "Panic of 1893." Colorado Encyclopedia, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/panic-1893. Accessed 03 February 2022.

[10] "Sherman Silver Purchase Act." Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherman_Silver_Purchase_Act#cite_note-lingley-1. Accessed 03 February 2022.

[11] Weiser, Kathy. "Ghosts of Cheesman Park." Legends of America, https://www.legendsofamerica.com/co-cheesemanpark/. Accessed 29 January 2022.

Comments